Photo credit: Tim Wheeler/People’s World

South Paris, Maine

Efforts to reform U.S. healthcare fall short. Preventable deaths are excessive, access to care is often impossible, costs are high, and profiteering thrives. Individual solutions replace common purpose. Hope lies with an activated working class fighting for equitable, accessible, humane, and effective healthcare.

Maine people are now collecting signatures for a petition on the 2026 ballot demanding that the state promote universal healthcare. The campaign coincides with costs of Medicare insurance premiums increasing after January 1, 2026. That’s when subsidies provided under the Affordable Care Act are reduced. The campaign will react also to recent federal legislation that removed a million or so low-income Americans from Medicaid coverage.

The precariousness of current healthcare arrangements is evident to Maine voters who are aware of a painful transition taking place in Lewiston, Maine’s second largest city, population 39,187. Lewiston’s Central Maine Healthcare corporation (CMH) has been losing $32.5 million annually over five years. California-based Prime Healthcare, the fifth largest U.S. profit-making health system and owner of 51 hospitals in 14 states, is buying CMH.

Takeover

Serving almost half a million people in its region, CMH operates Central Maine Medical Center (CMMC), two smaller hospitals in the area, and also physicians’ practices, urgent care offices, nursing homes, and counselling centers in 40 locations. CMMC, established in 1891, has 250 beds and employs 300 physicians representing most specialties. The agreement to change ownership, announced in January 2025, is about to be finalized.

Prime Healthcare will invest $150 million in CMH over 10 years, while assigning CMH to its Prime Healthcare Foundation, a supposedly non-profit entity with $2.1 billion in assets. Prime Healthcare has a record.

The corporation has periodically faced charges of overcharging, services dropped and safety standards ignored. After 2008, accusations surfaced in California of underfeeding hospital patients, allowing for post-surgery infections, and hospitalizing emergency room patients to increase revenues. Prime Healthcare in 2018 paid $65million in fines to settle accusations of Medicare fraud, over $35 million in 2021 for kickbacks and overcharging, and $1.25 million for false Medicare claims submitted by two Pennsylvania hospitals.

The Center for American Progress, a left-leaning think tank, recently warned against private equity companies owning health centers and controlling practitioners. It cited “unmanageable debt”, “increased costs for patients and payers,” poor patient care, and distressed healthcare workers.

Maine’s legislature on June 22 enacted legislation establishing a one-year moratorium on private equity companies (and real estate investment trusts) owning or operating hospitals in the state.

Troubles in city and state

Other Maine health systems are also experiencing big financial troubles. Northern Light Health, with debt of $620 million, recently closed an acute-care hospital in Waterville and announced a new partnership with the Harvard Pilgram system in Massachusetts. Lewiston’s St. Mary’s Health System closed its obstetrical services, sold off properties, and is laying off employees. The New England-wide Covenant Health system, owner of St. Mary’s since 1990, indicates covering the hospital’s unpaid bills amounting to $88 million is not “sustainable.”

One media report suggests Maine people aware of layoffs, health institutions’ financial troubles and diminishing services are “wondering about the future of their health care.” Medicaid funding reductions, shortages of primary care providers, and trimmed-down health centers have led to lengthy wait-times for appointments, long travel distances to new providers, and no care for many.

Lewiston, once a textile and shoe manufacturing center with a large population of French-speaking workers, migrants from Quebec, is “the poorest city in Maine.” Fallout from CMMC’s financial problems and reduced federal funding threaten the healthcare of people whose lives are already precarious.

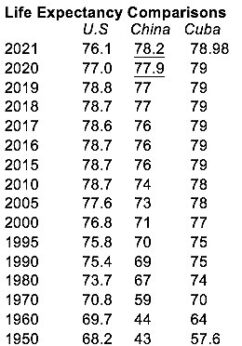

Eleven percent of Lewiston residents are migrants from Africa, mostly from Somalia. The 2023 poverty rate for the city’s Somali people was 32%. For Lewiston it was 17.7% and for Maine 10.4%. Poverty for Androscoggin County, which includes Lewiston, was 13% in 2023; child poverty was 16.6%. Life expectancy in Lewiston was 75.5 years in 2020, in Maine, 77.8 years.

Neither Maine or Lewiston is bereft of resources. Apart from remote rural and forested areas, Maine has well-functioning hospitals and competent practitioners. Experienced and concerned agencies and organizations provide social services and support for health-impaired Mainers.

Maine ranks 17th among the states in “cost, access, and quality of Medicaid and CHIP (Children’s Health Insurance Program) coverage for low-income individuals.” Another survey has Maine in 23rd place in “per person state public health funding” for 2023. A ranking of “states most supportive of people in poverty” puts Maine in 12th place.

Maine with its healthcare difficulties is not an outlier within the United States. Nevertheless, uncertainties prevail statewide, and Lewiston is in low-grade crisis mode. Planning is incremental, limited to localities, and accepting of the status quo. Collective action is not a consideration for those dealing with the crisis –providers, hospitals, recipients of care, and the general public. Individual initiative is the rule, as per U.S. habits.

Wider perspective

Those healthcare flaws and difficulties evident in Maine exist throughout the United States. Awareness of the consequences is crucial to building support for necessary change.

Too many people die. US infant mortality in 2021 ranked 33rd among 38 countries belonging to the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development, the world’s wealthiest countries. U.S. life expectancy in 2025 ranked 48th in the world. U.S. maternal mortality rate in 2023 was in 59th..

Inequalities are pervasive, as reflected in the poverty and life-expectancy variations in Maine. The huge flow of money through the system highlights inequality; it takes place at levels far removed from the depths of U.S. society. U.S. health expenditures per person in 2023 were $14,885; the average in other countries comparable by wealth was $7,371. Health expenditure as percent of GDP in US was 17.6% in 2023; the figure for all other wealthy countries was lower than Switzerland’s 12.0%.

Incentives for profiteering are many. While administrative costs represented only 3.9% of total Medicaid spending in 2023 and only 1.3% of all traditional Medicarespending in 2021, they accounted for “about 30%” of the cost of private health insurance in 2023. Presumably, profit-taking is embedded within those high administrative costs.

Critics of US healthcare, writing recently in Britain’s Lancet medical journal, assert that “profit-seeking has become preeminent.” They add that:

“Health resources of enormous worth … have come under the control of firms obligated to prioritize shareholders’ interests … The potential for profits has attracted new, even more aggressive corporate players—private equity firms … [These have] a single-minded focus on short-term profit” … The US health-care financing system makes profitability a mandatory condition for survival, even for non-profit hospitals.”

Realization dawns that adverse social and economic factors are tearing apart the benevolent purposes of healthcare. They make people sick. A report of the American Academy of Actuaries issued in 2020 says that, “30% to 50% of health outcomes are attributable to SDOH (social determinants of health), while only 10% to 20% are attributable to medical care.” A public health study shows that, “Nearly 45,000 annual deaths are associated with lack of health insurance.”

There is a way

That which has led to a floundering care system belongs to no one and weighs upon everyone, more so on the dispossessed and marginalized. It’s an epidemic, in the original Greek meaning of that word, “upon the people.” Corrective action would therefore derive from and apply to all people all together. Healthcare itself supplies the model.

For many, physician John Snow is the “father of public health.” In London in 1854, Snow investigated an outbreak of cholera, a water-borne infectious disease. Suspecting that water from the Broad Street pump was the culprit, he removed the handle. The epidemic stopped. He had acted preventatively on behalf of the many, not for individuals.

Comes the Cuban Revolution and preventative and curative medical care are joined in one public health system. Political change allowed for that.

Rudolf Virchow (1821-1902), pathology giant and one of the founders of scientific medicine, was on the case almost two centuries earlier. This leader of the Berlin Revolutionary Committee was behind the barricades in the revolutionary year of 1848. In 1847-1847, Virchow studies a typhus epidemic killing inhabitants of Upper Silesia. He notes in his report that:

“A devastating epidemic and a terrible famine simultaneously ravaged a poor, ignorant and apathetic population. … No one would have thought such a state of affairs possible in a state such as Prussia, … we must not hesitate to draw all those conclusions that can be drawn. . . I myself … was determined, … to help in the demolition of the old edifice of our state. [The conclusions] can be summarized briefly in three words: Full unlimited democracy.”

Virchow writes that, “Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale… The physicians are the natural attorneys of the poor.”

If democracy was the fix then for an epidemic, it’s the fix now for the current epidemic of disordered healthcare. The people themselves would rise to the occasion. And how are they going to do that?

The role of profiteering in U.S. healthcare is a reminder of the capitalist surroundings of the struggle at hand. Aroused working and marginalized people are on one side and the rich and powerful on the other.

Does capitalism need to go in order that healthcare changes? Not yet, suggests international health analyst Vicente Navarro. In explaining U.S. failure to achieve universal healthcare, he observes that, “The U.S. is the only major capitalist developed country without a national health program, and without a mass-based socialist party. It is also one of the countries with weaker unions, which is to a large degree responsible for the lack of a mass-based working-class party.”

That clarifies. The working class is crucial to repairing a dismal situation. Its partisans will work on strengthening the labor movement in size and militancy. Working class political formations will have their day.

Martin Luther King has the last word. Speaking to health workers in 1966 King remarked that, “Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane because it often results in physical death.” His reference to “forms of inequality” implies the existence of the capitalist system giving rise to such forms. Capitalism fosters early deaths as well as racism.

W.T. Whitney, Jr., is a political journalist whose focus is on Latin America, health care, and anti-racism. A Cuba solidarity activist, he formerly worked as a pediatrician and lives in rural Maine.