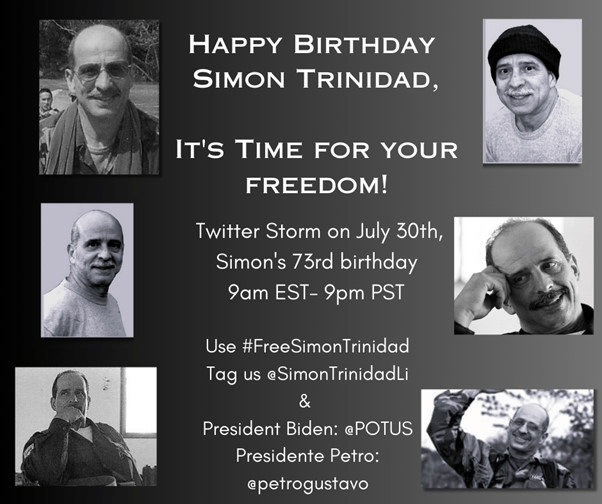

“Simon Trinidad” and Piedad Cordoba (Image: Piedad Cordoba)

South Paris, Maine

The title recalls the title of Henry David Thoreau’s essay “A Plea for Captain John Brown.” Trinidad, like John Brown, is remarkable for his implacable resolve and regard for justice.

Trinidad was 58 years of age when a U.S. court in 2008 sentenced him to 60 years in prison. His alleged crime was that of conspiracy to hold hostage three U.S. drug-war contractors operating in Colombia. In effect, he is serving a life sentence. He had nothing to do with the hostage-taking.

The contractors, captured in 2003, went free in 2008. U.S. drug war in Colombia has obscured the big U.S. role in Colombia’s war against leftist insurgents, primarily the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

Simón Trinidad was a FARC leader. The FARC and Colombia’s government signed a peace agreement in 2016 and Trinidad and other ex-combatants expected to be part of a peace process. Now he is a prisoner in a super-max prison in the United States and is confined to his cell for all but two hours per day, receives no mail, and is allowed very few visitors.

On July 27, Simón Trinidad unexpectedly was a featured item in the news in Colombia. An undated letter he had written to Colombian chancellor Álvaro Leyva requesting repatriation to Colombia had appeared on social media. News reports were reproducing it.

Observers associated Trinidad’s letter with the U.S. government’s announcement the day before that the bloodthirsty former paramilitary chieftain Salvatore Mancuso, also jailed in the United States, soon would be extradited to Colombia. President Gustavo Petro designated Mancuso as a “promotor of peace.”

Trinidad, not so favored as this, in his letter wrote of his determination to testify before the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, as other former FARC combatants have done, and Mancuso too, virtually. This court, established under the Peace Agreement of 2016, offers former combatants an opportunity to tell the truth about crimes they may have committed during the civil war and, having done so, to be pardoned or punished.

Trinidad apparently hopes not only that that Chancellor Leyva will inform the U.S. Secretary of State of his request to be repatriated but also that his message will be passed on to President Biden, who has the power to release him from prison.

Progressive Colombian Senator Iván Cepeda, “one of the people who speaks of peace on behalf of President Gustavo Petro,” welcomed “Simón Trinidad’s proposal [and] sent it directly to Chancellor Álvaro Leyva.”

Trinidad had joined the left-leaning Patriotic Union (UP) electoral coalition after it formed in 1985. A year later, paramilitaries began their massacre of UP adherents that, with impunity from Colombia’s government, lasted for years. In response, Trinidad in 1987 joined the FARC and, in the process, dropped his name Ricardo Palmera Pineda. For the FARC, Trinidad was responsible for political education and propaganda and was a negotiator.

The U.S. government in 2000 introduced its “Plan Colombia” through which Colombia’s military secured U.S. weapons and training assistance; U.S. troops and military contractors were deployed in Colombia. The appearance of Plan Colombia doomed peace negotiations between the FARC and Colombia’s government that were in progress at the time.

As a lead FARC negotiator in those talks, Simón Trinidad became known to international observers. His course with the FARC ended abruptly on January 2, 2004, when Colombian military personnel and the CIA seized him in Quito. Trinidad was there seeking UN assistance for a proposed prisoner exchange.

Colombia’s government extradited Trinidad to the United States on New Year’s Eve, 2004. According to his U.S. lawyer Mark Burton, Trinidad’s U.S. captors regarded him as a “trophy prisoner.”

Trinidad’s U.S. handlers had to stage four trials for them to finally gain a conviction. His capture and his multiple appearances in U.S. courtrooms from 2005 to 2008 served as real-time advertising that testified to U.S. commitment to anti-insurgency war and drug war in Colombia.

Trinidad’s misfortune was to have fallen into the clutches of a nation whose record on prisoners is horrific. After all, “The United States stands alone as the only nation that sentences people to life without parole for crimes committed before turning 18.” (No wonder: of 196 countries, only the United States has yet to ratify the UN’s Convention on the Rights of the Child.)

As a U.S. political prisoner, Simón Trinidad harks back to the Scottsboro Boys, who in Alabama faced death penalties in the 1930s; to Communist Party members jailed under the Smith Act; to Black Panther Party members caught up in the U.S. government’s COINTELPRO project. Simón Trinidad is also representative of prisoners gathered up in U.S. wars and other interventions abroad. They include: Ricardo Flores Magón, Mexican revolutionary who died in Leavenworth Federal Prison in 1922; the “Cuban Five” prisoners who resisted U.S. hostilities against Cuba; and the unfortunates ending up in the U.S. prison in Guantanamo during and after the Iraq War.

Despite the Peace Agreement, paramilitaries or other thugs have since killed almost 400 former FARC fighters; 300 FARC prisoners of war are still in prison almost seven years later.

Violence in the countryside persists. Colombia’s military is unable or unwilling to suppress a new breed of paramilitaries. One report highlights the paramilitaries’ “symbiotic relationship with Colombian state actors.” Declassified State Department and CIA documents from George Washington University’s National Security Archives say the same. The plot thickens: the tight relationship between the U.S. and Colombian militaries and the U.S. alliance with Colombia’s government together suggest U.S. complicity with a violence that Colombia’s Army and state are unable or unwilling to control.

The bad news for Simón Trinidad is that the U.S. government is betting not on peace in Colombia, but on continuing war. For that reason, Simón Trinidad confronts formidable barriers in satisfying his need to join Colombia’s peace process. Mark Burton’s words end this report: “Simón Trinidad is a man with a clear vision for a new Colombia, a Colombia in peace and with social justice. Colombia needs to listen to his voice, his vision, his proposals for peace. His continued imprisonment in the United States on false charges is an insult to Colombia, its history, and its people.”

Burton’s comments appear in a remarkable new eBook, accessible here. It contains commentary, in Spanish, from activists, writers, and intellectuals seeking Trinidad’s repatriation. The announcement of this book offers a video presentation, here, of reflections and documentary material.

W.T. Whitney Jr. is a political journalist whose focus is on Latin America, health care, and anti-racism. A Cuba solidarity activist, he formerly worked as a pediatrician, lives in rural Maine. W.T. Whitney Jr. es un periodista político cuyo enfoque está en América Latina, la atención médica y el antirracismo. Activista solidario con Cuba, anteriormente trabajó como pediatra, vive en la zona rural de Maine.