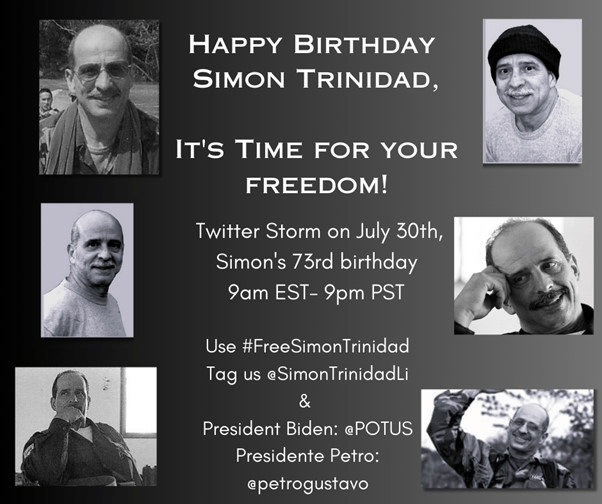

Simón Trinidad, leader of the former guerrilla organization Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia. File photo / via Orinoco Tribune

South Paris, Maine

President Biden recently pardoned his son Hunter Biden and commuted the sentences of 1499 drug offenders. Analyst Charles Pierce insists Biden should pardon Simón Trinidad also. Here we join this plea on behalf of the Colombian Ricardo Palmera, whose nom de guerre is Simón Trinidad. Biden indeed must release Trinidad and let him return to Colombia.

Trinidad, a former leader of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), has been imprisoned since 2008. U.S. agents arranged for his capture in Ecuador in 2003. Charged with drug-trafficking, Trinidad was extradited from Colombia to the United States in late 2004. Juries in two of his four trials there failed to convict him of narco-trafficking. Two trials were required to convict Trinidad of terrorist conspiracy to hold hostage three U.S. military contractors operating in Colombia.

The Peace Agreement of 2016 between Colombia’s government and the FARC offered a process for combatants to leave war behind. The Agreement produced the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), a device whereby Trinidad, once he arrives in Colombia, would be able to tell the truth about participating in civil war and possibly gain immunity from further punishment.

Trinidad’s defenders claim that his earlier experience as a negotiator on behalf of the FARC amply qualify him to help with overcoming difficulties still damaging prospects for peace in Colombia.

Trinidad is presently serving a 60-year sentence – 20 years for each of the captured North Americans. Early release from prison for Trinidad would make partial amends for an excessively long sentence and relieve him of the cruelty marking his prison experience.

President Gustavo Petro’s Colombia’s government is now finally pressuring the Biden administration to return Trinidad to Colombia. A note sent from the Colombian Embassy on November 12 proposes that “in a humanitarian spirit and for the purpose of [Trinidad] contributing to Colombia’s peace agenda, we present a request for a presidential pardon.”

In a request first made in early 2023, Colombia still seeks “necessary technical facilities” provided for Trinidad so that he might participate in “virtual sessions” of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace. Once repatriated, he could then participate fully in “the search for total peace in Colombia.”

The U.S. government, ironically enough, has expressed support for the peace process in Colombia, both during four years of negotiation and subsequently after the Agreement was signed in 2016.

Simón Trinidad came from a wealthy, politically powerful, and landowning family in Cesar Department in northern Colombia. He prepared as an economist. Before he joined the FARC in 1987, he was managing an agricultural bank and his family’s estates, and teaching at a local university.

In reaction to accentuation of class-based bloody conflict in Colombia’s rural areas, ongoing for decades, his politics changed. Joining with others, he opposed the Colombian government’s tolerance of paramilitary killings of office-holders and adherents of the Patriotic Union electoral coalition, from 1985 on. They were Communist Party members, former FARC guerrillas, and other progressives. Well over 5000 of them would be massacred.

Within the FARC, Trinidad attended to political education, propaganda, and negotiations with foreign agencies and political leaders. He served as a lead negotiator and spokesperson during the failed FARC-Colombian government peace negotiations taking place in San Vicente del Caguen in 1998-2002.

Here are good reasons for Trinidad’s U.S. imprisonment to end, and for him to return to Colombia now:

· The federal prison in Florence, Colorado where Trinidad is held “is one of the strictest maximum-security prisons in the world.” He remained in solitary confinement for 12 years. Authorities restrict his outside communication to infrequent contacts with a very few family members. Visits are few and far between.

· The conspiracy charge against him amounts to no more than membership in the FARC. That insurgency sought revolutionary social change. International law recognizes both the right of revolution, and rights for prisoners of war.

· FARC guerrillas in 2003 shot down the plane carrying the three U.S. military contractors and took them hostage. They were “three retired military officers who provided intelligence services through private companies.” The FARC regarded them as enemy combatants. They went free in 2008. Simón Trinidad was far-removed geographically and command-wise from the decision to bring down their plane. In view of such circumstances, Trinidad’s 60-year jail sentence is wildly disproportionate.

· Mind-reading has its hazards, but appearances may be suggestive. Pains taken to prosecute and persecute Simón Trinidad speak to his status as “trophy” prisoner for his U.S. captors – as indicated by Trinidad’s U.S. attorney Mark Burton. Under the pretext of drug war, the U.S. government in 2000 had introduced its “Plan Colombia” program of military assistance directed at ridding Colombia of leftist insurgents – to the tune eventually of $10 billion. Simón Trinidad’s prominent role in the recently failed Caguen peace talks showed off Plan Colombia as meeting expectations; an exalted prisoner like Trinidad was now in U.S. hands.

There would be the possibility too that Trinidad had earned the special ire of the entitled classes in both Colombia and the United States. Born with a silver spoon, he was indeed a traitor to his class.

SimónTrinidad as a special case is clear on comparing his fate with that of major paramilitary boss Salvatore Mancuso, reliably accused of killing 1500 Colombians. Each faced trials in the United States after extradition on narco-trafficking charges. Mancuso served his 15-year sentence and in February 2024 was allowed to return to Colombia. President Gustavo Petro honored him through an appointment as “peace manager as part of’ [his] ‘Total Peace’ initiative.” Mancuso, but not Simón Trinidad, has testified before the JEP.

Attorney Mark Burton regards Trinidad as a friend: “To know him is to admire him, because he is an intelligent, human man, and also very firm in his political and social ideas. There are not many people like him in life. He is a person that in the worst prison in the United States they have not been able to break him. He is a person with firmness, ideas, and character. That alone is worth admiration.”

W.T. Whitney Jr. is a political journalist whose focus is on Latin America, health care, and anti-racism. A Cuba solidarity activist, he formerly worked as a pediatrician, and lives in rural Maine.