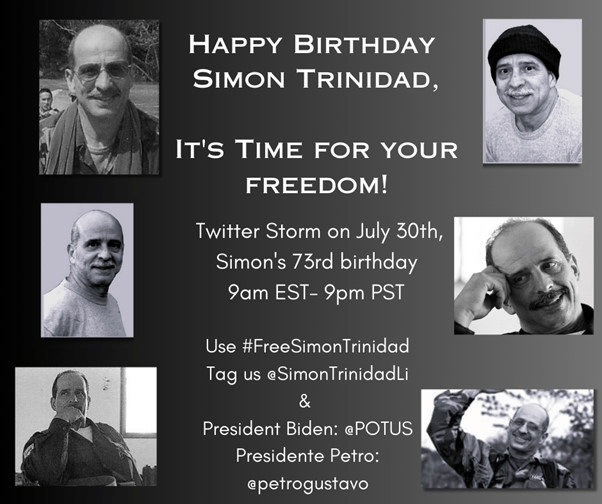

Surrounded by supporters, Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro, center, holds a sign that reads in Spanish, ‘The Agrarian Reform is Unstoppable,’ during a rally to show support for his proposed reforms, in Bogota, Colombia, Sept. 27, 2023. | Fernando Vergara / AP

South Paris, Maine

Colombian president Gustavo Petro on October 3 attended a big meeting of mostly small farmers in El Tambo, in Cauca, where “the coca economy is the main way of life for thousands of peasants.” Colombia’s first progressive president ever was presenting his government’s National Drug Policy for 2023. Petro had insisted earlier that “war on drugs has failed.” He recently expressed support for “phased decriminalization.”

His government is evidently prioritizing the present initiative, which is part of its far-reaching program for social and political reforms, now stumbling due to strong right-wing political opposition. The drug plan attends to main features of Colombian’s longstanding social disaster. They include: dispossession leading to consolidation of large land holdings, agricultural underdevelopment, migrations leading to precarious lives often in cities, widespread lethal violence; and great wealth accumulated by top-level distributers and their financial backers.

The government’s new plan promises much, especially to working people both in Colombia and abroad. Freed of the monopolization of illegal drug production and commercialization, rural areas might shift to diversified agricultural production and expanded support systems. Prospects for community-development programs might improve and those rural Colombians forced into cities might return.

By reducing that fraction of the domestic and international economy represented by drug production and marketing, the government would, in effect, be redistributing wealth, to a degree. And any success the new plan achieves in cutting back on drug commercialization might translate into reduced visibility abroad and, consequently, into lessened appeal to U.S. interventionists who have often justified military intrusions on that basis.

The plan calls for 27 “territorial spaces” in 16 departments and in Bogota, along with 51 “inter-institutional or bilateral technical working-groups.” Each one would hold three conferences with strategic allies, five with sectors drawn from the Joint Committee on Coordination and Follow-up. Other gatherings would involve women, young people, and prevention specialists.

Government spokespersons focused on the program’s two pillars. One of them, called “oxygenation,” supports those “territories, communities, people and ecosystems” adversely affected by drug-trafficking. It would support the transition to legal economies and reduce “vulnerabilities of regions and populations.” Measures would be taken that advance “environmental management and climate action toward … restoring regions” adversely affected by the narco-economy. The personal use of “psychoactive substances” will be dealt with on the basis of public health and human rights.

The other pillar, called “asphyxiation,” targets “the strategic nodes of the criminal system that generates violence” and “profits most from this illegal economy.” The object would be to interfere with the “capacities and income” of the strongest drug-trafficking organizations and to do so so “systematically” and with consideration “of their complexity and relation with other economies both legal and illegal.” Persons involved in production and trafficking would benefit from destigmatization and social justice.

The new plan has a slogan: “sewing life and burying narco-trafficking.” The aim is to remove 222,400 acres from coca and marihuana cultivation, reduce cocaine production by 43%, and block at least $55 billion in illegal financial gains. The plan would interfere with irregular banking and financial maneuvers and reduce both deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions.

Colombia’s illegal drug industry remains well entrenched, despite the drug war waged from 2000 on under the auspices of US Plan Colombia, a venture that absorbed billions of U.S. taxpayer dollars. A United Nations report cites a 13% one-year increase in land given over to illegal crops, as of 2022. It takes note of a recent “summit meeting [in Bogota] of narcotrafficking capos from Albania, Poland, Spain and Colombia.”

The relentlessness of cocaine and marihuana production in Colombia may have led the U.S. government to recently stop monitoring the acreage of illegal crop cultivation. Indeed, after four decades of involvement, the U.S. government has abandoned its war against narco-trafficking in Colombia, according to analyst Aram Aharonian. Still, he reports, “weapons manufacturers” are benefiting, along with workers whose livelihood depends on narco-trafficking.

Petro’s new drug policy is significant mostly because it pursues objectives of the 2016 Peace Agreement which ended armed conflict between Colombia’s government and the FARC insurgency. Important parts of the new drug plan coincide with major provisions of that Agreement that were never implemented.

Agrarian reform matches with improving rural life generally. Solving the illicit drug problem was a goal of the Peace Agreement and now is the essence of Petro’s plan. The guarantee under the Peace Agreement of safety for former combatants never took root. The attacks against them are largely related to drug-trafficking, and now that will be dealt with.

Violence has been, and remains, pervasive. During just 13 months of the Petro government, assassins took the lives of 198 community and human-rights leaders and 43 former combatants.

A comprehensive report on the Petro government’s shepherding of the peace process highlights the association of continuing violence with narco-trafficking. Indeed, “broad regions of the country” see persisting collusion of the police and military with paramilitaries and with “smaller narco-trafficking gangs and narco-trafficking structures.”

Affirmation of the Petro government’s new campaign against drug trafficking comes from the report in June of the United Nations Mission to Verify the Peace Agreement. It emphasizes “the importance of peace initiatives and of efforts being made to expand the presence of the state so that vulnerable communities may be protected, especially in rural areas.”

Much is at stake as a government undertakes to control and end the production and marketing of illegal drugs. According to the UN’s Economic Commission for Latin America, “Problems associated with the production, trafficking, and consumption of drugs in Latin America affect the population’s quality of life, contribute to forms of social exclusion and institutional weakness, generate much insecurity and violence, and corrode governance in some countries.”

W.T. Whitney Jr. is a political journalist whose focus is on Latin America, health care, and anti-racism. A Cuba solidarity activist, he formerly worked as a pediatrician, lives in rural Maine. W.T. Whitney Jr. es un periodista político cuyo enfoque está en América Latina, la atención médica y el antirracismo. Activista solidario con Cuba, anteriormente trabajó como pediatra, vive en la zona rural de Maine.