By W. T. Whitney Jr.

It didn’t seem to fit. The website of the Colombian Communist Party on October 5 published an article in which author Félix León Martínez MD recharacterizes a disease. Martínez quotes extensively from an editorial appearing in the famous British medical journal Lancet. There, editor Richard Horton MD claims that COVID 19 is a “syndemic” rather than a disease.

A disease manifests signs and symptoms. Usually causation and treatment of a disease are familiar. COVID 19 has signs and symptoms too, but Martínez and Horton say that as a syndemic, COVID 19 has causes and treatment methods that are still unknown. In his article, Martínez draws from Horton’s editorial to study the COVID 19 situation in Colombia. The present report aspires to do likewise in regard to the United States. We explore how the insights of both authors apply to managing the disease.

Martínez, who is an academic investigator specializing in social protection and public health, maintains that “the [COVID 19] pandemic, although in principle a phenomenon of biological origin, affects each nation differently, according to the political, economic and social organization it has established.” His article’s title is “From Pandemic to Syndemic: Poor Prognosis.”

Horton, as quoted by Martínez, states that, “We have viewed the cause of this crisis as an infectious disease … But … the story of COVID-19 is not so simple. Two categories of disease are interacting within specific populations—infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and an array of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). These conditions are clustering within social groups according to patterns of inequality deeply embedded in our societies. The aggregation of these diseases on a background of social and economic disparity exacerbates the adverse effects of each separate disease.”

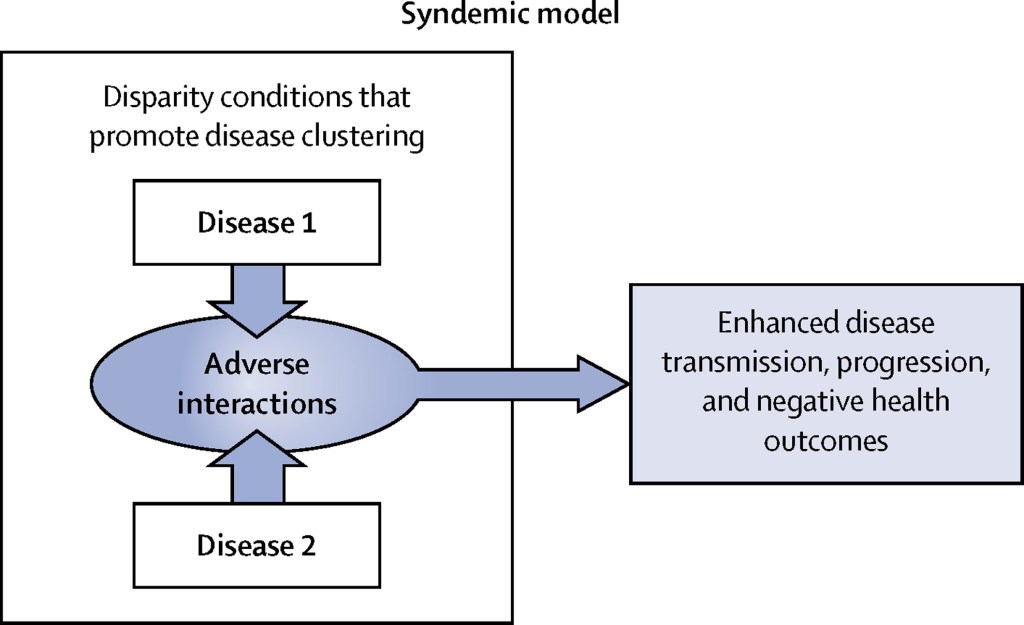

As described by Horton, “Syndemics are characterized by biological and social interactions between conditions and states, interactions that increase a person’s susceptibility to harm or worsen their health outcomes … The hallmark of a syndemic is the presence of two or more pathological states that interact adversely with each other, adversely affecting the mutual course of each disease trajectory.” COVID-19, is more than a pandemic.

Horton observes that, “For the world’s poorest billion people today, Noncommunicable Diseases (NCDs) account for more than one-third of their disease burden.” And, “The most important consequence of seeing COVID-19 as a syndemic is to highlight its social origins. The vulnerability of older citizens, black, Asian and minority ethnic communities, and key workers, who are commonly underpaid and have fewer social protections, points to a hitherto barely recognized truth, namely that no matter how effective a treatment or protective vaccine is, the search for a purely biomedical solution to COVID-19 will fail.”

In his article Martínez highlights Colombia’s extreme economic inequalities. For example, 10% of landholders own 82% of the productive land, and soon “three of every five persons in Colombia will be living in a state of precariousness or poverty,” and “24% of the vulnerable middle class will fall again into poverty.”

He notes that even before COVID 19 appeared in Colombia, mortality was increasing from heart attacks, cerebrovascular illnesses, and hypertension – the three major causes of death – and from diabetes. And these conditions, plus obesity, had become more frequent. Too many Colombians were finding healthcare to be inaccessible and/or of poor quality. Martínez points out that on being infected with COVID 19, the chronically ill are highly susceptible to terrible sickness and even death.

At this writing, nearly 29,000 Colombians have died from COVID 19, The case fatality rate is 3.1%, the 10th highest in the world. Martínez cites a recent poll indicating that 16% of people in Bogota lack food and that 65% of households there include at least one person who is unemployed due to COVID 19.

Similarly in the United States, societal dynamics determine the likelihood of dying from COVID 19. According to the CDC, Blacks, Indians, and Latinxs face at least 2.6 times the risk of being infected by COVID 19 as do white people. And COVID 19 death rates for Indians and Blacks are 1.4% and 2.1% greater, respectively, than the rate for white people.

But according to epidemiologist Sharrelle Barber, writing in the Lancet, “Blacks comprise 13% of the US population but roughly one quarter of COVID-19 deaths and are nearly four times more likely to die from COVID-19 compared to whites … Blacks across all age groups are nearly three times more likely than white people to contract COVID-19.”

Prior to the arrival of the virus, Black people and Latinxs were already more likely than whites to die from cancer, diabetes, hypertension, chronic respiratory disease, and other noncommunicable diseases. Their life expectancy at age 50 is significantly reduced, compared to U.S. whites. As with Colombians, their burden of chronic ill health becomes dangerous on being infected with COVID 19. Multiple studies highlight the racial discrimination and racist attitudes that often limit their access to healthcare or the quality of care they receive.

The average African American family income in 2018 was $41,361; for white families, $70,642. The poverty rate for African Americans that year was 20.8%, more than twice that of whites. Indeed, poverty alone predisposes Blacks and Latinxs to serious illness or death from COVID 19. Low income often translates into lack of insurance or inability to pay; African-Americans may have no regular healthcare provider. Their work and housing situations frequently allow for easy exposure to the virus. Nevertheless, effects of low income and racism often merge, and are not easily separated for study.

Ideally, healthcare practice is collaborative. Physicians regularly seek help from colleagues knowledgeable about unusual medical conditions or skilled in special treatment methods. They seek consultation. Editor Richard Horton was advising infectious disease specialists themselves to seek consultation as they deal with COVID 19. Specifically: “Limiting the harm caused by SARS-CoV-2 will demand far greater attention to NCDs and socioeconomic inequality than has hitherto been admitted [and] Unless governments design policies and programs to reverse the deep disparities, our societies will never be truly safe from COVID-19.”

Both Horton and Martínez were inviting political practitioners – politicians and the people’s movement – to participate in fashioning all-encompassing programs of prevention and treatment. Also, in publishing Martínez’s article, the editors of the Colombian Communist Party website were, in effect, calling upon healthcare workers to attend to a sick society and, doing so, know who their consultants would be. These would include Communists and socialists who have advanced skills in this area.