Tenants’ rent strike banners on the Cargill Falls Mill | credit: Tamara Rudic, Katy Slininger, and Lily F. Spot, illustration inspired by SftPer Matteo Farinella’s original design.

Reposted from Science for the People

Introduction: The Horizon of Solidarity Science

The question of how to practice “science for the people” should be a focus for all radical scientists, and indeed it has been a driving force behind the development of the New Haven chapter (SftP-NHV) since its inception one year ago. As capitalism continues to degrade the basis of a dignified existence in full view of the world’s working people, the need to recommit to a radical anti-capitalist approach is as obvious as ever. Determining where to channel these efforts remains a challenge. In many ways, our current moment is defined by the dissolution of working class institutions, such as militant unions and workers’ parties, that existed through much of the twentieth century. This decomposition—and the accompanying decline in the tradition of radical science —leaves scientists with few spaces to participate in political struggle.1 The recent surge of unionization in higher education has been an encouraging development. However, scientists’ participation in union movements does not necessarily require a class analysis of science itself. At the same time, class struggle encompasses much more than workplace unionization. Therefore, we must begin to relearn the practices that can mobilize science effectively in support of the working class and its recomposition (i.e., its rehabilitation into a unified class organized against capitalism). In other words, how can we practice science as class struggle?

In Connecticut, the recent development of the statewide tenant union movement provided the most obvious inlet into an active terrain of class struggle. By building on existing relationships with tenant unionists, specifically with the Cargill Tenants Union (CTU) in Putnam, CT, we were able to mobilize scientific resources in support of CTU’s effort to secure abatement of high levels of lead contamination in their homes. While developing this project, we were introduced to the idea of “solidarity science”2 by comrades in the Western Massachusetts chapter of SftP, which posits that scientists should not only work for but with the people, whose experiences and understandings are necessary for a science that addresses social needs and advances justice. Inspired by this, we aim to practice science in solidarity with class struggle(s), applying the skills and tools of science in struggle with the working class, resisting service-based models that often plague the attempts of scientists to intervene in social issues. In this vein, we have sought to develop an organizing project that deploys scientists as agents in class struggle.

In this article, we provide an overview of the development of this specific struggle, our development as an organization, our intervention in this fight, and the political and practical lessons we have learned. In our view, this provides a first step for engaging scientists in the process of class recomposition in parallel with the reemergence of socialist, working class institutions and organizations.

Development of the Cargill Tenants Union: Organizing around Lead and Mold Contamination on the Path to a Wildcat Rent Strike

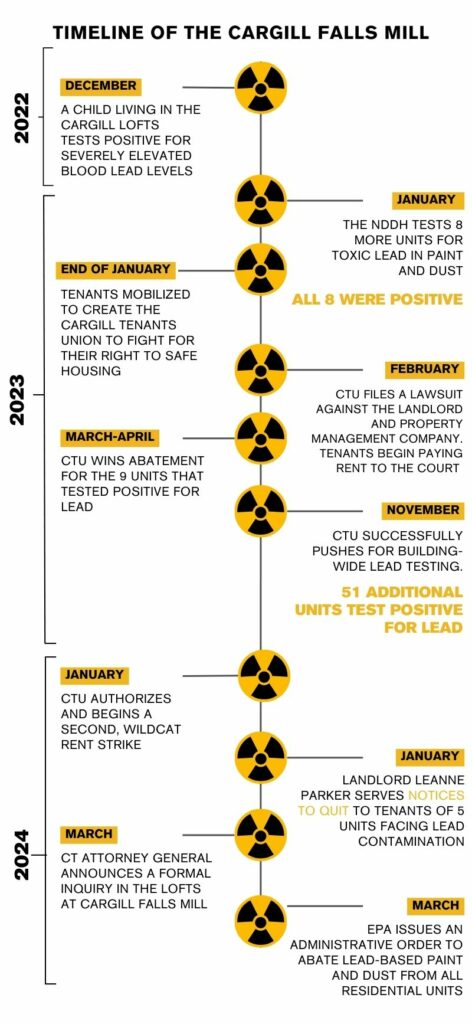

The Lofts at Cargill Falls Mill in Putnam, CT opened its doors to tenants in 2020 with the promise of fulfilling local affordable housing mandates.3 Putnam is a small post-industrial exurb in the northeast corner of the state, detached from urban centers. Millions in federal and state subsidies were granted to the developer and landlord to renovate the nineteenth century textile mill, turning the Brownfield site into mixed-income housing. The property owner, Leanne Parker of Historic Cargill Falls LLC, is also behind a shadow “green energy” LLC operating the mill’s hydropower system. Both LLCs received federal and state grants to subsidize remediation and construction. Yet in December 2022, only a couple years after the complex opened, tenants were notified by the Northeast District Department of Health (NDDH) that a toddler had been poisoned by shocking levels of lead found in the family’s unit. Lead dust levels on the floor of the apartment were almost 5,000 times the level considered hazardous by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). While lead paint, and resulting toxic dust, is expected to be found in buildings older than 1978—the year that US regulations around the use of lead paint were introduced—Cargill Falls Mill was a recently renovated property. NDDH subsequently tested the eight units in the building with young children and all units had hazardous levels of defective lead paint, lead dust, or in most cases both. Some of the children in these apartments already had elevated Blood Lead Levels (BLL).

Due to the acute risks to young children, concerned parents organized the first few tenant meetings. A supermajority of tenants voted to form the Cargill Tenants Union (CTU) in January 2023. As they organized members, tenants uncovered more chronic issues including pests, cracking drywall, crumbling bricks and masonry, water-damaged load-bearing wood, stagnant moisture and leaking, and toxic mold conditions. The early development of CTU as a union was greatly supported by the Connecticut Democratic Socialists of America’s (CT DSA) Housing Justice Project (HJP), Connecticut Fair Housing, and tenant union locals affiliated with the Autonomous Tenants Union Network (ATUN).

Due to the extreme dangers present together with the landlord’s refusal to communicate, within a month of getting organized, CTU members went on their first rent strike.4 From February to August 2023, tenants followed Connecticut’s legal process of paying rent into escrow accounts under the local housing court. CTU served a letter to both property management and the landlord with the following demands: comprehensive lead and mold inspections throughout the complex, swift abatement of health hazards, proper maintenance staffing, and structural repairs. The only units that had received lead inspections were those housing young children at the time of the initial lead discovery, and the landlord was refusing to inspect additional units. The Putnam housing court ended up dismissing cases filed by tenants without lead inspections, circularly citing the lack of evidence of lead contamination in these apartments. Understaffing and disinvestment by municipalities in Windham County resulted in the NDDH failing to enforce lead regulations and lacking the capacity to monitor the situation.

Nevertheless, CTU’s first rent strike won a rent freeze into 2024, comprehensive lead inspections paid for by the CT Department of Housing, air quality inspections, mold and lead abatement in some units, and renewal of leases for vulnerable tenants. The few families that relocated for abatement were fairly compensated, thanks to union demands.

Tenants received the results of union-won lead inspections in November 2023: the majority of tested apartments and common areas had toxic lead levels, and some children were still living in unabated units. Media coverage had dwindled, tenant turnover led to multiple rounds of union reorganization, and the initial strategy of filing housing court cases to force repairs had lost traction. At this point, the CTU organizing committee recognized a need and opportunity to escalate their fight against the landlord. In order to rebuild the union, organizers knocked doors in the complex over the winter holidays, sharing health and hazard information that had been withheld from tenants. After several member meetings and individual organizing conversations, CTU decided to pursue a rent strike for the second time. Members were asked to sign a pledge to withhold rent outside of the established housing court process—collecting the money themselves. The majority of tenants feared retaliatory evictions too greatly to attempt another rent strike, but supported the action as signatories on the new demand letter. A group of a dozen tenants, those willing to risk housing court, authorized a wildcat rent strike beginning in January 2024. The landlord immediately retaliated by serving Notices to Quit (an “eviction notice”) to members withholding rent, but not before tenants brought national attention to their struggle.

Integrating SftP-NHV into Regional Class Struggle

The New Haven chapter of SftP came together in late spring 2023 around the desire to build a community of scientists with radical politics at Yale University and in the greater New Haven area. We began very intentionally from a position of not confining ourselves to the Yale community, which we felt was not only inconsistent with our politics, but risked compromising the anti-capitalist character of the organization. A desire emerged within the chapter to develop an explicit organizing project. As many of the participants in the chapter at this time were scientists or academic workers, the notion of “citizen science,” or “community science” was a natural extension of this desire.

We were already aware at this time of various critiques of the typical “non-profit” disposition of many community science projects, that neither applied a class analysis to their work nor developed the leverage necessary to enact change around an issue outside of petitioning legislators, city governments, etc. The ineffectiveness of the already-existing lead regulations in the state underscored our decision to avoid time-consuming and minimally impactful projects focused on policy change. We also benefited from the broader SftP community which was able to share various practical insights into the development of such a project. It was in many ways a fortunate coincidence that the question of how best to approach a community science project from a class struggle perspective arose in the midst of heightened tenant unionism across the state of Connecticut.

A crucial element in the development of our work was an ongoing relationship between our members and tenant unionists in CTU. It was the establishment of this basis of trust and comradeship that enabled a collaboration to blossom. But, more importantly, this relationship was a prerequisite for identifying the tenant union struggle as a site to implement solidarity science as such. That is, we were already aware at this time that CTU was organizing around the issue of lead and mold contamination in their building, and we saw in this fight the opportunity for applying scientific skills and resources to advance their struggle. We therefore formed the Lead and Mold Contamination Working Group within SftP-NHV as the organizational locus of the chapter for participating in this struggle.

It is worth noting that our first instinct in this regard was to attempt to divert university resources (instrumentation, expertise, etc.) toward CTU’s organizing. For example, we attempted to locate scientific instrumentation that would allow us to measure lead from samples taken directly from the Cargill Falls Mill. There may yet be some merit to this approach; however, not only were we met with institutional opposition and political indifference, we understood that any measurement we produced, no matter how rigorous, was unlikely to be treated with the same authority as a state-certified inspection result. We therefore considered how we could implement our individual skills to advance the tenant union’s ongoing organizing work.

Data Analysis as Agitprop and Infrastructure for Autonomous Tenant Organization

Initial analysis of the data took a technical, practical, and exploratory form—converting the data to a usable format, understanding the values we were looking at and where they came from. Next, we determined some basic questions that would prove useful in better understanding the extent and nature of the lead contamination. As we progressed, more salient questions arose: How were we to think about data in a way that ensured participation in struggle with the tenants rather than as a service-oriented project? Our experience and training as scientists primes us to think in particular modes that are not always amenable to tenant struggle. A political lens on data analysis led to the emergence of the following tangible uses: enriching the existing organizing infrastructure maintained by the tenants, practical health and safety applications, and agitprop.

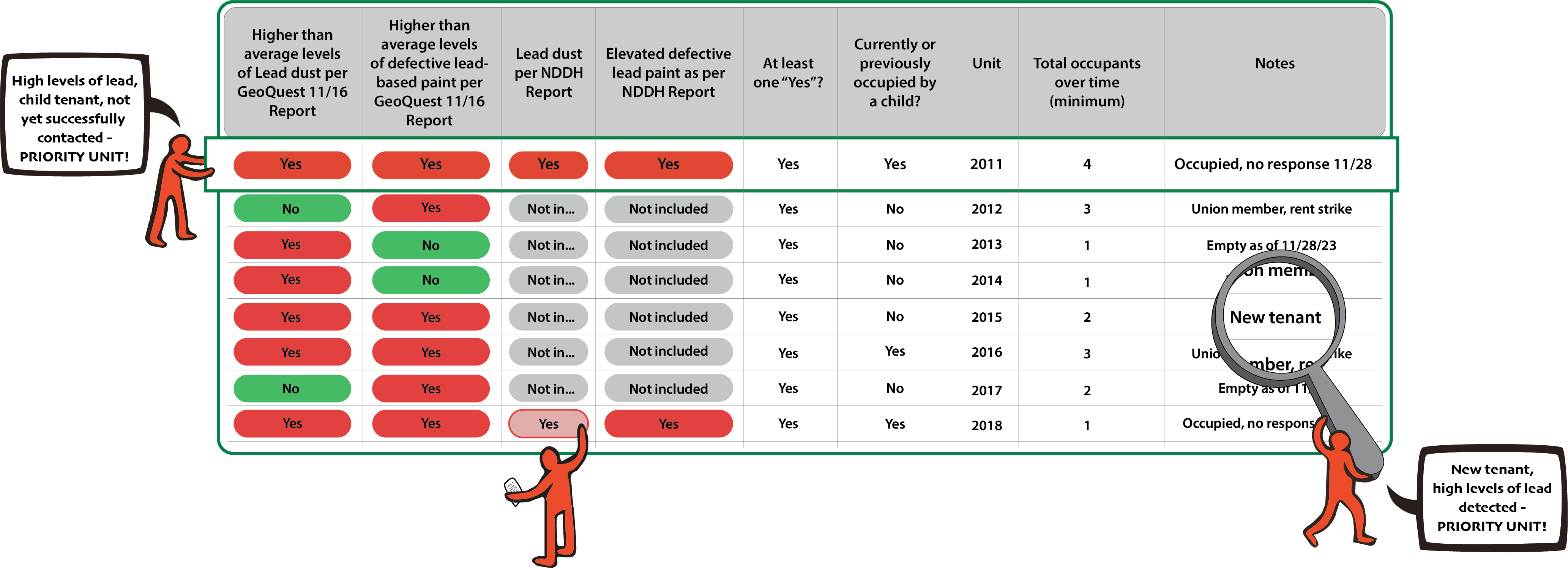

Access to the tenant organizing database was a catalyst for making the data politically useful. Each row features a unit in the complex with columns for demographic information on tenants, their status as union members and rent strike participants, and further organizing notes. We were able to integrate the testing and abatement data for each unit and the benefits of this method became immediately apparent. High priority apartments for one-on-one organizing conversations were identified: for example, a tenant who had not yet opened the door for union conversations was found to have some of the highest lead dust levels in the building. Immediate attention was brought to specific health concerns, including high levels of defective lead paint identified in a child’s bedroom, the risks of which had not been properly communicated to the family in that unit. While petitioning institutions and the courts was not a goal for our project, the work we put into sorting and processing documents proved valuable to investigators from the EPA and pro-bono lawyers representing tenants.

The incorporation of the testing information into the database also allowed us to generate graphics that made the need for intervention transparent and urgent, leveraging the data visualization skills of working group members. We were able to clearly state, expose, and disseminate the number of affected units and the minimum number of people and children who had been living in conditions with toxic lead, something that no government agency, landlord, or even the testing company was able to do.5

Throughout the politicized data analysis process, we were able to emphasize the contrasting manner of data use by the property management, landlord, local health department, and testing and abatement companies: they were obscured, inaccessible, and without utility to tenant needs. Even after the tenants won comprehensive lead testing, they were simply given a 1,312 page document with minimal interpretation and no guidance on how to proceed in order to protect themselves. Despite the majority of units in the building testing positive for dangerous levels of lead dust or paint, months later no abatement had occurred and the path to proper abatement remained unclear. Moving forward with a radical analysis and use of data allowed our work to advance the principles of radical science. We firmly rejected the idea that data analysis is an apolitical or unbiased venture, seeking to expose the bias of existing data collection and interpretation practices with the goal of enabling CTU’s militancy. Politicizing the lead inspection data transformed an inert and opaque dataset into a powerful organizing tool.

This was a rapidly changing situation with respect to both the needs of the tenants and the information available to us. What had started as a project to potentially complete DIY lead testing turned into a data-heavy project when the tenants won comprehensive testing. On more than one occasion, tenants would be surprised by unannounced, insufficient, and hazardous abatement work being completed by a company not even insured to abate historic properties. Tenants reported to us that the owner of the abatement company would show up without warning in an otherwise unmarked van with an “Infowars” sticker to set up shoddy abatement worksites, which on at least one occasion resulted in injury to an elderly tenant. Thus we would often shift gears from the data, to information gathering, to academic literature searches on lead hazards and best practices for abatement.

It is insufficient to simply transplant scientists from the academy into class struggles. Many scientists must be properly politicized, which we believe requires their development as agents in class struggle first, and as scientists second.

Our ability to carry out analysis of the situation was directly proportional to the organizing pressure applied by the tenants, in terms of getting the testing done, the documentation maintained by the tenants, the intra-union relationships between tenants, and the extent of public outreach. Underlying all of this, it was of utmost importance that our analysis be shaped around the organizing strengths and needs of the tenant project, not the other way around.

What can tenant organizers look for in these types of collaborations? This was a tenant project ripe for a collaboration with a team of radical scientists. Our advice to tenants seeking scientists to join their struggle is to find those who hold radical perspectives and have organizing experience—while this does not describe the majority of scientists, we are out there and growing as a force.

Practical and Theoretical Outcomes: Class Agency as the Basis for Solidarity Science

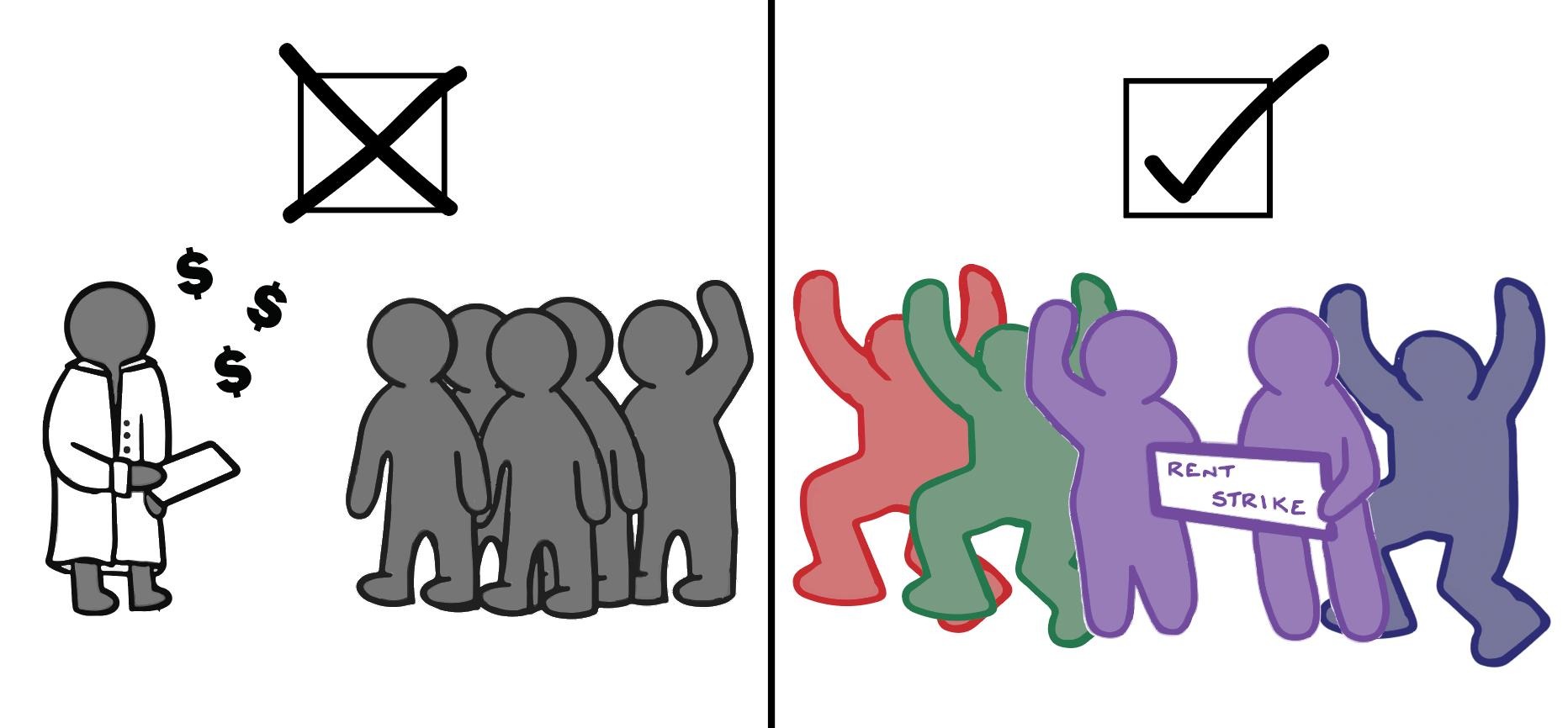

We began this article by asking how we could practice science as class struggle. We can now provide a cursory answer to this question. We should first account for a clear tension in the basic notion of “class struggle science,” which is that the ostensible class position of scientists (academic or otherwise) is often tangential to the working class. Scientists are trained in deeply “de-politicized” environments. Even within the academic labor context, they often occupy an ambivalent, if not reactionary, fraction within union struggles.6 Thus, it is insufficient to simply transplant scientists from the academy into class struggles. Many scientists must be properly politicized, which we believe requires their development as agents in class struggle first, and as scientists second.

The cultivation of class agency requires both political education and direct experience in the working class. This serves two important functions: first, it protects solidarity science projects from infiltration by liberal elements that will turn our efforts away from base-building and class struggle toward toothless petitioning and legislative campaigns. Second, it creates the basis upon which the necessary relationships between scientists and working class institutions engaged in struggle can be built. If we identify as scientists first, and as agents in class struggle second, we risk falling into the same elitist, exclusive trappings upon which the entire university edifice is constructed. Our goal should always be to supplant this edifice with the horizon of solidarity science.

This perspective stems from our own organizing backgrounds and experiences. We feel strongly that our work, and the political analysis that has developed from it, would not have been the same had we not had the benefit of decades of prior organizing experience collectively: within unions (both leadership and rank-and-file), prison abolition movements, student activism, tenant organizing (from canvassing to the robust involvement described above), environmental justice, reproductive justice, and more. Intentionally positioning ourselves as agents of class struggle informed the development of our project not as charity or service, but as an important and novel appendage of the ongoing tenant organizing efforts of CTU.

Solidarity Science: What Is to Be Done?

While each organizing context is unique, here we hope to emphasize characteristics that can inform tenant organizers and radical scientists interested in developing a similar collaboration. Our involvement in CTU’s organizing became more valuable as it became more apparent that the local public health infrastructure was inadequate. The NDDH lacks sufficient resources due to depleted municipal investments and thus is unable to reliably fulfill the basic legal mandates for inspections and enforcement. The local hospital is in disrepair, there are no shelters for the unhoused, and there is no public transit. This stands in stark contrast to more developed municipalities with more robust public health infrastructure; thus, such factors should be taken seriously in evaluating the terrains of struggle and goals of similar organizing projects in different locales. Nevertheless, canvassing of similar renovated mills in larger towns in CT (which chapter members participated in) revealed that the lead and mold contamination at Cargill Falls is not an isolated issue. In fact, we think lead contamination may be endemic to these properties, many of which have been renovated by the same developer(s).

In addition to the politicized data analysis, there was a knock-on benefit provided by the “legitimacy” that scientists could offer to CTU’s cause. Our involvement, and the credibility that came with it, was a boon to CTU’s organizing because we could offer relevant expertise. We do not wish to convey that it was our expertise alone that made us useful to this struggle—we had no formal, institutionalized experience or training in dealing with lead contamination, lead poisoning, etc. In alignment with the principles of solidarity science, the tenants were in many ways experts in their own situation. However, institutional bias in favor of scientific and technical expertise can be directed politically to benefit political struggle.7

Because Putnam has no active political base or advocacy groups, we were also able to support CTU’s organizing by doing data-heavy administrative work. This was vital not only to the lead contamination case the tenants were making, but also in providing support to otherwise geographically and politically isolated organizers. In this way, we expanded the capacity of CTU directly, while simultaneously developing the political nature of the struggle.

We would be remiss not to acknowledge the historical legacy within which our work has developed. It is no coincidence that the original manifestation of SftP in the 1970’s developed the Technical Assistance Program (TAP) in Boston, MA, which mobilized scientific expertise to prevent the construction of a highway over a vulnerable neighborhood, and collaborated with the Boston chapter of the Black Panther Party to install an electrical generator to provide power to medical clinics. As long-time SftP member Herb Fox wrote in 1970, “TAP is one of the ways to put the slogan ‘Science for the People’ into practice.”8 Contemporaneously, the Young Lords staged an occupation of the Lincoln Hospital in New York City’s South Bronx to draw attention to health disparities in the largely black and Puerto Rican community.9 The Lords also ran “The Lead Offensive,”10 an effort to identify instances of lead poisoning in their communities. The Lords were trained by medical doctors at the Metropolitan Hospital in East Harlem to perform lead screening tests, finding one third of the children they tested to have lead poisoning. By bringing national attention to the issue, they were able to provoke the implementation of more rigorous lead testing in their communities. Along with additional efforts like “The TB Initiative,” which screened for tuberculosis infections via takeover of a city X-Ray truck, the work of the Lords provides a profoundly inspiring example of solidarity science in action more than 50 years ago that we should reflect on in our movements today.

Ultimately, our collaboration with CTU solidified their project as a socialist one. Because we began our work with the recognition of CTU as a sovereign political entity, our collaboration only served to deepen our collective political analysis and tactical approach. When compared to more typical collaborations that might emerge—say, with non-profits or local electeds—our collaboration heightened the most relevant aspects of CTU’s struggle and informed and supported their most militant endeavors, rather than subordinating them to the interests of outside organizations. In support of the wildcat rent strike, the “Rally to Defend CTU” convened organized tenants, labor unionists from AFSCME (American Federations of State, County, and Municipal Employees), socialists, lawyers, and scientists. The development of this coalition should serve as an example not only for building the political and social infrastructure required to win organized struggles against bosses and landlords, but also as a guiding principle for how radical scientists can engage in such struggles: as active participants, not philanthropists.

As a result of CTU’s organizing, the Connecticut Attorney General formally opened an inquiry into the landlord’s possible misuse of state and federal funds, originally granted to her for remediation of hazardous materials, hydropower conversion, and provision of affordable housing.11 Most recently, the EPA has intervened in the lead abatement process at the Lofts at Cargill Falls Mill, issuing a monumental Administrative Order against Leanne Parker and investigating violations of federal regulations.12 Some families are still on rent strike, and several tenants beat back their eviction cases and successfully negotiated to stay in their homes. These developments are a testament to the organizing efforts of CTU, and we encourage radical scientists everywhere to imagine a place within these struggles. We all belong to this fight, and indeed, we have a world to win. ♦

All the artwork above are collectively credited to Tamara Rudic, Katy Slininger, and Lily F. Spot illustrations are inspired by SftPer Matteo Farinella’s original design.

Acknowledgements:

This project was truly a group effort of the Lead and Mold Working Contamination group and we would like to thank all members, especially Tamara, Josh, Malcom, and Lily for their contributions to data cleanup, analysis, methodology, and graphics. We benefitted greatly from early conversations with comrades in the broader SftP organization including Edward Millar and the Western Mass chapter including Sigrid Schmalzer. We would also like to thank Tatiana Cheeks for coordinating the donation of air purifiers to protect tenants from mold.

Notes:

– Liz Mason-Deese, “From Decomposition to Inquiry: Militant Research in Argentina’s MTDs,” Viewpoint, September 25, 2013.

– “Making Science Work for Social Justice,” Science for the People—Western Massachusetts, Online workshop.

– Stephen Beale, “Cargill Falls Mill development in Putnam opening to residents,” The Bulletin, August 2, 2020; Putnam Affordable – – – Housing Ad Hoc Committee, Town of Putnam Affordable Housing Plan 2023-2028 (April 19, 2023).

– Ginny Monk, “They found lead in their apartment complex. But who is responsible?,” CT Mirror, August 15, 2023.

– SftP-NHV and Cargill Tenants Union, Instagram post, February 29, 2024.

– Trent McDonald and Jewel Tomasula, “STEM Organizing in Waves: A Macro and Micro View,” in Organize the Lab: Theory and – – —– Practice, ed. Science for the People (Knoxville: People’s Science Network, 2022).

– Michael Sainato, “The Connecticut Residents Holding a Rent Strike amid Lead Poisoning Crisis,” Guardian, March 27, 2024.

– Herb Fox, “Technical Assistance Program,” Science for the People 2, no. 2 (August 1970): 7.

– Johanna Fernández, The Young Lords: A Radical History (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2019).

– Fernández, Young Lords.

Ginny Monk, “CT Attorney General Probing Lead, Hazards at Putnam Apartments,” CT Mirror, March 7, 2024.

Vincent Gabrielle, “EPA Cites Troubled Putnam Housing Development for Complex-Wide Lead Issues” CT Insider, March 27, 2024.

Monthly Review does not necessarily adhere to all of the views conveyed in articles republished at MR Online. Our goal is to share a variety of left perspectives that we think our readers will find interesting or useful. —Eds.

Nick Pokorzynski is a scientist, socialist, and co-founder of the New Haven chapter of Science for the People.

Emily Sutton is a scientist, organizer, and co-founder of the New Haven chapter of Science for the People.

Katy Slininger an artist, mother, and founding member of the Cargill Tenants Union in Putnam, CT. She is a member of Connecticut Democratic Socialists of America and DSA’s Communist Caucus.

Tamara Rudic is a science communicator with a passion for environmental justice. She lives with two beautiful tuxedo cats, is an avid forager, and is a lover of sci-fi.